» home » portfolio » reportage

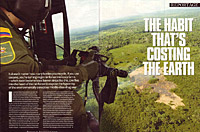

The habit that's costing the earth

It doesn’t matter how many bottles you recycle. If you use cocaine, you’re turning virgin rainforest into coca farms – which soon become toxic barren strips like this. Live flies into the heart of the rainforest to expose the hypocrisy of the environmentally conscious middle-class drug user

In a drone of Bell Huey turbines we clear the razor wire and sandbagged machine-gun emplacements of the base, flying low while casting a racing black shadow over the landscape. We head north-west into hostile territory. The machine gunner on my left flicks a red switch on the 7.62mm six-barrelled minigun and a green

LED shows the system is armed. Belts of dull brass bullets stretch back into the bowels of the chopper. Sitting behind an inscrutable black visor, which reflects the topography below, he begins to scan the forest and ramshackle houses nestling on riverbanks for snipers lurking in the jungle drifting 500ft beneath my feet, as the chopper blades emit a pulsating whump.

Twenty minutes earlier, as we pulled on flak jackets, pilot Captain Carlos Suarez Amador of the Colombian anti-narcotics police had warned, ‘We were shot at today and yesterday. In Colombia, it all looks nice and everything is OK, then all of a sudden it changes and trouble happens.’

He gestured to the hangar behind us, containing one of the police force’s battle-scarred aircraft. A machine gun had torn through the left wing, ripping apart the aileron. Amador is a kindly, fresh-faced man who believes earnestly in what he’s doing, but he doesn’t underplay the risks. ‘Every day we’re taking fire now. In a second we could lose the gunner or the pilot.’

The brutal 40-year war in Colombia, the world’s biggest exporter of cocaine, is intensifying. The damaged plane was being flown by an American pilot as part of a US-financed initiative known as Plan Colombia.

More than $6 billion has been spent over the past eight years in an attempt to destroy the coca crops that keep the guerrillas and drug cartels in business.

The military base is in the dusty town of San José del Guaviare, a cocaine-trading hot spot deep in the south of the country. Until recently, it was controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (aka the Farc), left-wing guerrillas who currently hold an estimated 700 hostages and are waging a brutal insurgency against the government. Last year, 900 civilians were killed in the fighting.

Not so long ago, you could buy your groceries or fill up your car by paying with cocaine paste in San José. Around 40 cocaine traffickers were caught in the town by police last year alone. But the army has driven the guerrillas out of town and into the jungle bordering Ecuador and Venezuela.

Nevertheless, rebels still ambush patrols and plant roadside bombs. One improvised device, made from a gas cylinder packed with explosives, killed a policeman last August; another was discovered just before Christmas. One pilot told me there’s a rumour swirling around the base that the Farc pays a reward for anyone who shoots an American in the town…

As San José fades beneath us, the countryside changes into an endless, lush rainforest. Hot, sweaty jungle air blasts through the open door of the helicopter and an aroma of fertile earth seeps into the cabin. The jungle is so dense that when US special forces tried to sweep it for hostages with thermal-imaging cameras, their hi-tech systems couldn’t penetrate the canopy.

The territory we’re flying over is controlled by right-wing paramilitaries led by notorious drug trafficker Daniel ‘El Loco’ Barrera. His lieutenant is nicknamed ‘Cuchillo’, meaning ‘knife’, because he used to be a butcher and enjoys dispatching his victims with a blade.

‘The further we go the more dangerous it gets,’ said Amador before we left. Aside from the dangers of snipers and paramilitaries, who would capture us were we to be shot down, the area is also dotted with landmines.

Above is a dome of clear blue sky; below us the luscious green rainforest unfurls like a huge carpet to the endless horizon, just part of the 200,000 square miles of Colombia’s jungle. After 20 minutes we fly over the foothills of the Andes mountain range and on over the Macarena National Park, an area of dense rainforest that’s home to a cornucopia of species, including 18 per cent of the world’s bird species and a vast number of amphibians. The verdant jungles floating beneath us on the equator are the lungs of the world, supplying 15 to 20 per cent of the planet’s oxygen. But as we fly overhead, a spreading cancer is clearly visible.

The death and bloodshed meted out by the drug barons obscures the huge environmental damage being caused by the cultivation of coca. Ironically, the demand for cocaine is being fuelled by middle-class professionals – social drug users who shout their green credentials with Greenpeace stickers on their Toyota Prius hybrid cars, but are unwittingly aiding the destruction of the jungle. For every gram of cocaine bought in the West, 4.4 square metres of this diverse forest are lost forever.

There’s a crackle in my helmet as Amador makes clear he’s going to dive. ‘Now you will see the damage to my country,’ he says. This should be an area of pristine beauty, one of the most remote parts of the world. Instead, the Macarena National Park is pockmarked with patches of burnt-out land. Huge swathes have been scorched; areas of charred wood and drifting smoke from forest fires dot the landscape as cocaine traffickers slash and burn to clear the jungle for new coca plantations. Neat rectangles have been torn out of the forest. Hectares of land that contained 750 types of tree and 1,500 species of plant have been razed to the ground. Irreplaceable trees, many more than a thousand years old, lie dead on their sides in hazy brown patches. As we dip and roll, we can see clearings where only one type of electric-green plant is growing.

A few minutes later, the gunner swings around to aim his weapon at a shack below us. We buzz over the corrugated-iron roof of a cocaine ‘kitchen’ where paste is produced. The shack is surrounded by overturned blue barrels leaking the noxious chemicals – including sulphuric acid and petrol – that are used to produce cocaine. Two minutes later we fly over a rural schoolhouse that’s infested with coca plants. ‘They put them near a school so we can’t fumigate them or shoot at them,’ Amador tells me later.

Unusually, this part of the forest is deemed so precious that the Colombian Government won’t fumigate cocaine crops here for risk of harming the fragile environment. Instead, they use manual ‘eradication teams’, who walk in rows pulling out the coca plants by hand while US UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters hover overhead. Despite these precautions, they’re often shot at by snipers, and last month one team came across a booby-trapped coca plant. When it was tugged out of the ground it set off a colossal bomb that left a five-metre crater – and six people dead.

If you’re one of the million people in Britain who takes cocaine then you’re one of those responsible for this destruction. Cocaine use has quadrupled in this country in the past decade, according to the British Crime Survey, to the point where 45 tons of the drug is imported annually. More than 2.6 per cent of the population between the ages of 16 and 59 have used cocaine, compared with 0.6 per cent just over ten years ago. Britain is now second only to Spain as the biggest user of cocaine in Europe and is the world’s third biggest user of the substance.

So far, the cultivation of coca has led to the destruction of 5.4 million acres of tropical rainforest in Colombia, an area roughly the size of Wales. For every three hectares destroyed, only one produces coca.

Ironically, the fight against cocaine is pushing the coca growers deeper into the rainforest. It’s a battle being fought not just by the Colombian authorities but also by the British taxpayer. The British Government won’t disclose how much it spends on the war against drugs in Colombia, but according to sources the money given to the Colombian Government to support its battle is ‘substantial’.

I meet Colombia’s Vice-President, Francisco Santos Calderón, in his plush offices in Bogotá. He’s wearing a sleek suit and has an assistant light his cigarettes for him while he reclines on an expensive brown leather sofa. In 1990, he was kidnapped by the Medellín Cartel, a network of drug traffickers led by Pablo Escobar, and held for eight months. After his release he set up a campaign group to help victims of kidnappings – hostages and families. A decade later he had to leave the country for two years when he received death threats from the Farc.

Now, as Vice-President, his most passionate cause is fighting the destruction of the Colombian rainforest. He is determined to be heard by British cocaine users, who he sees as particularly switched on to the green message. ‘In the past 15 years we’ve lost millions of hectares of rainforest to coca production,’ he spits angrily. ‘I mean, how much is one hectare of rainforest worth? I bet it’s more than four kilograms of cocaine.

‘For somebody who drives a hybrid, who recycles, who is worried about global warming – to tell him that a night of partying will destroy four square metres of rainforest might lead him to make another decision.

‘When coca arrives in an area, it’s like the seven plagues have arrived – violence, prostitution and money. Coca arrives and communities are destroyed; they see violence that they have never seen, money that they have never seen. The communities get uprooted and the jungle is destroyed.’

Across the city in a high-rise government building is Hector Hernando Bernal Contreras of the Narcotics National Agency, a donnish man who probably knows more about cocaine than anyone else in Colombia. He has risked his life to get to cocaine labs in the jungle.

He can tell you how the traffickers cut their product with industrial quantities of the blood-pressure drug diltiazem to open up the coronary arteries in the heart so that the cocaine hits quicker, and then add other pharmaceuticals that increase the numbers of receptors in the brain so the drug acts more quickly. He has little pity for those who choose to take it, but feels passionately about one of Earth’s greatest natural resources being destroyed so people can enjoy the ‘champagne of drugs’.

‘You can’t make an estimate of the damage done in Colombia due to cocaine production,’ he says. ‘We are totally destroying one of the richest ecosystems on the planet, with incredible biodiversity. Cocaine is produced in virgin rainforest, areas that contain ten per cent of the planet’s plant and animal life. It’s a chronic problem. We are talking about 30 years of production. There is no doubt we’ve lost species that have never been found; if you don’t know what you have, then you don’t know what you have lost.’

Experts estimate that the world loses 137 animal and insect species every day to deforestation. Worst of all, the rainforest holds crucial secrets to finding treatments for cancer and Aids; cures that may be lost forever. The US National Cancer Institute has identified 3,000 plants active against cancer cells, and 70 per cent of these are found in the rainforest.

The blue motorcycle tears past our car for a third time, throwing up a plume of terracotta dust behind it. The rider, his face obscured with a bandanna and a helmet, peers inside our car once again. For the past 20 minutes he has been repeatedly riding past and looking in at us. Each time he has slammed to a stop in a dust cloud and started gabbling into his mobile phone.

My guide and translator turns an ashen colour, and Flaviano, the man leading us out to the coca fields, turns in the front seat, a distinct look of unease crossing his features. We’re heading beyond the safe confines of San José into a rural area where the Farc operate to see a coca field from the ground. Flaviano is worried that an informant has told the guerrillas he has spotted a foreigner – a prime target for kidnapping. We stop the car, quickly having to decide if we should get out of here as soon as possible.

Flaviano is a short, compact man who bears a striking resemblance to the main character from the Super Mario video games. He’s made his living growing coca and selling it to either the paramilitaries or the Farc guerrillas. He’s seen friends and family murdered and kidnapped in front of his eyes. Every month he has to pay ‘taxes’ to the Farc, who control the area.

He only agreed to take us to the coca fields on the condition that we travelled in an unmarked car. ‘Don’t come with the police or in an armoured car,’ he said. ‘If you do there will be trouble. Just come quietly with me.’ But now it looks like we might be caught anyway by paid informants. ‘It’s always the one you least expect, the nicest one in the village, who will inform on you,’ says Flaviano.

The motorcycle roars past again, and Flaviano catches a glimpse of the rider. He cracks a relieved grin. ‘It’s OK,’ he says. ‘I know him. He has cocaine he’s trying to sell, but he can’t meet the buyer because the army is around.’ We’d seen a US Black Hawk thrumming low over the fields as we drove out of town.

We press on, jouncing down a primitive sandy road before turning off down a track and coming to a halt. Flaviano leads us down a jungle trail before we find ourselves in a field of coca. The plants are spindly stalks about waist-high with soft, green leaves. It seems amazing that something so innocent could be responsible for so much death. ‘We the campesinos (growers) are always in the middle,’ says Flaviano. ‘You sell to one group and then the paramilitaries are angry you didn’t sell to them and then the other way around.’

Both groups have an insatiable hunger for the drug, and the price has shot up in the past few years to $1,000 a kilo. ‘The paramilitaries paid $400, so then the guerrillas paid $1,000,’ says Flaviano. He misses the ‘golden days’ of the Nineties, when ‘American drug dealers would come to the village with suitcases full of money’.

Nearby is a shack where Flaviano used to transform the leaves and extract the psychoactive substance, benzoylmethylecgonine, otherwise known as cocaine. To get the alkaloids out of the leaves he would dump them in a huge rusty tub of petrol, where they would break down into paste. The paste is sold to armed groups, who transform it into cocaine powder.

It takes around 70 noxious chemicals to turn coca leaves into cocaine. Traffickers use vast quantities of solvents, potassium permanganate and sulphuric acid. The chemicals end up dumped into rivers, poisoning fish and anyone who drinks the water. Around 720,000 water sources have been polluted. In 2005, Colombian authorities seized eight million kilos of illegal chemicals en route to secret cocaine labs, ultimately to be spewed out into the forest.

The area around the shack is a scene of massive destruction. There are rusty barrels and the earth has been scorched from sulphuric acid and petrol; a few acres look as though they’ve been napalmed. ‘They fumigated us so we burned everything down afterwards,’ says Flaviano.

Only now, after undergoing government education programmes, does Flaviano appreciate the impact cocaine production has on the environment. ‘We didn’t realise the damage we were doing for future generations,’ he says with a shrug. I ask him if he ever took cocaine himself.

The coca producers protect their crops with landmines, often made for as little as $15. This is not only a further threat to the environment, but also to the local people. In 2007, Colombia had the highest number of landmine victims in the world.

At the Centro Integral de Rehabilitación de Colombia, in a Bogotá suburb, Richard Villadiego, 28, a skinny-limbed man, talks in a gentle mumble about the landmine that destroyed his life. He was a gold miner, walking back from work down a trail he had taken every day for years.

‘I was half an hour from my house, then all I remember is an explosion. When I tried to get up, I realised my leg had been blown off.’ He crawled to a nearby house. Seventy villagers took him to hospital in a journey requiring both a boat and a helicopter. There he had his right leg amputated below the knee. He’d expected his hand to be amputated, too, but doctors were able to rebuild it.

‘There are so many landmines everywhere that you cannot work the land,’ he says.

One of the men responsible for the landmines and the destruction I have witnessed gives me a vice-like handshake. His stocky, hulking frame blocks the sunlight streaming through the door as we’re escorted outside into a compound with 30ft razor wire and a concrete floor.

This is La Picota, Bogotá’s maximum-security prison. Above us on rooftops, guards in navy blue fatigues with assault rifles patrol the walkways. Raul Aguledo has spent his life murdering and kidnapping, trafficking cocaine and fighting a guerrilla war against the government as a mid-level Farc commander. Now he’s a government collaborator, the Farc want to kill him. Prison is a refuge. We are joined by his guerrilla colleague Luis Chadoro, a small man with a razored skull, thick stubble and a nervous demeanour.

Both men give an insight into the dark heart of the Farc’s operation. ‘The ecosystems have been destroyed by the development of the war in this country,’ says Aguledo. ‘Cocaine labs are always near rivers. They use gallons of chemicals like sulphuric acid. We cannot destroy those chemicals because they are so strong.’

‘The chemicals from the labs are dumped into the rivers where the animals go to drink,’ adds Chadoro.

Aguledo says the Farc are constantly on the move, slashing out camps for upwards of 80 men. ‘When we came back through, all the water sources and rivers had dried up,’ he explains. ‘People don’t realise the great damage they are doing with deforestation.’

But Aguledo reserves most scorn for the international companies who export, sometimes illegally, the chemicals needed for industrial-scale cocaine production. He fixes me with an angry gaze, then lays the blame on European companies. ‘I want you to promise me that in this article you are going to tell the truth about the people of this country. Colombia has been overtaken by the profits from cocaine and it has caused thousands of deaths. The people who are responsible for the thousands of dead are the multinational companies who produce these chemicals.’

He’s also critical of the Government’s fumigation programmes, which he has experienced first-hand. ‘When they fumigated we saw dead monkeys, iguanas and sometimes even cows, horses and dogs. They fumigate everything. Once I was sprayed and I had a terrible headache. My comrades were vomiting as well.’

The Colombian authorities are adamant, however, that fumigation is the lesser of two evils. I am shown around the San José spraying operation, which each day covers an area of 300 hectares in ongoing sorties. Hundreds of plastic barrels containing the weedkiller glyphosate and Cosmo-Flux, a chemical that helps the weedkiller ‘stick’ to leaves, are piled high.

A 2005 report by the Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD) stated that the risks to the environment from fumigation were ‘small’, and the hazard to humans was judged to be of ‘low risk’.

The continuing ecological devastation in Colombia will only be stopped when for campesinos such as Flaviano there are alternatives to growing coca. But coca is always grown in remote areas, which means if they turn to alternatives such as pineapples, there’s no distribution route to take them to market. Some in Colombia feel that cocaine should simply be legalised. As one local told me, ‘Why should we die here so that everyone else can take cocaine and have fun?’

Calderón hopes raising awareness of the environmental impact of cocaine will encourage those in Britain taking the drug to be more responsible for the world they’re damaging. He explains why the issue is so important to him. ‘We tried making the connection between a drug consumer and a landmine or a kidnap victim here, or a displacement or a car bomb,’ he says. ‘But the British and Europeans see drug consumption as a personal choice.’ In other words, people didn’t care about the loss of human life. ‘But with this message,’ he continues, ‘people will realise that cocaine is a curse to the environment, to their environment.’

From leaf to line ...

- Coca leaves are harvested every 45 days or so.

- The leaves are dried, shredded and placed in a plastic-lined pit with ammonia and lime. Petrol or diesel is added; this acts as a solvent that extracts the water-insoluble cocaine alkaloids.

- The liquid is drained off and more ammonia is added, precipitating the cocaine alkaloids. At this stage the mixture is a white milky fluid.

- More petrol is added as well as sulphuric acid. The liquid is filtered through fine cloth and the precipitate collected. More ammonia is added to form a sticky white paste that can be rolled into balls or pressed into pats. This is the cocaine paste.

- The paste then has to be processed into cocaine base. This involves adding hydrochloric acid and potassium permanganate.

- The final stages of processing require even more skill and equipment, so the base is often made into cocaine in its destination country. In Britain, alcohol or acetone is added along with hydrochloric acid to form the product sold on the streets.

Words and pictures by Jonathan Green